Power Transformers: A Comprehensive Guide to Design and Maintenance

An electrical device that is static is a power transformer. It is essential to the distribution and transfer of electrical energy. Transferring electrical power between circuits at varying voltage levels is its main function. Electromagnetic induction is used for this transfer, and the power system's frequency remains unchanged.

The function is essential to the effective transmission of electricity over long distances. Modern power grids would not be feasible without transformers due to the significant energy losses that come with low-voltage, long-distance transmission.

Two Main Operational Modes

Step-Up: Located at power plants. Power is increased from the low generator voltage, which is usually between 11 and 25 kV, to the extra-high transmission voltage, which can reach up to 765 kV. This is done because the square of the voltage is inversely proportional to the power loss that occurs during transmission. By drastically lowering current, raising voltage minimizes heat loss.

Step-Down: Found at the main substations. It reduces the high transmission voltage to distribution or sub-transmission voltage levels (e.g., 138 kV down to 34.5 kV). The power for the last distribution networks that supply cities and industries is prepared by this process.

Power transformers are vital assets that need careful monitoring because they are made to run constantly under full load.

Classification and Structural Types

Power transformers are primarily classified by their application within the power grid. They are also categorized by their internal core structure.

Classification by Application

The biggest and most potent devices are transmission transformers (Generator Step-Up, or GSU). They connect power plants to the grid by running at the highest voltages and are built for maximum efficiency and low loss.

In order to provide stability and redundancy, interconnecting transformers, also known as tie transformers, are used to join two distinct voltage systems within the main transmission network.

Distribution Transformers: The last connection to customers, these are smaller. They lower the distribution voltage to 120V or 240V, which are safe service voltages. Although they are optimized for low-load situations, they are usually made with a slightly lower efficiency than transmission units.

Classification by Core Construction

The type of core depends on how the windings and core material (silicon steel laminations) are put together.

Core-Type Construction: The magnetic core limbs are surrounded by windings, or coils. Usually, applications requiring extremely high voltage and where superior insulation is crucial use this structure. Typically, the coils are concentric, meaning that one coil is inside the other.

Shell-Type Construction: The windings are surrounded and enclosed by the magnetic core. High-current applications and smaller distribution transformers frequently use this design. Superior mechanical strength is provided by this structure to resist short-circuit forces.

Detailed Components and Protection Systems

In addition to the basic windings and core, a power transformer includes several sophisticated components for cooling, insulation, and protection.

Main Tank and Core Assembly

The active components (core and windings) are submerged within a rugged steel main tank. The tank's primary role is to hold the insulating oil and the active parts.

Insulating Oil and Cooling System

Transformer oil serves as both a coolant and a major electrical insulator. The cooling system is classified based on how the oil and external air are circulated. There are three primary cooling methods utilized in power transformers:

ONAN (Oil Natural, Air Natural): In this setup, convection causes the air outside the radiators and the oil inside the tank to circulate naturally. For smaller to medium-sized units with controllable heat generation, this technique is employed.

Oil Natural, Air Forced (ONAF): This technique uses fans to push air over the radiators while maintaining a natural internal oil circulation. Larger units needing more cooling capacity can use this configuration because the forced air significantly speeds up the rate of heat removal.

OFAF (Oil Forced, Air Forced): In the largest and highest-load transformers, pumps are used to force the oil circulation through the cooling units, and fans simultaneously force air over the radiators. This double-forced system provides the maximum heat dissipation and is reserved for the biggest, most critical units.

Ancillary Protection Devices

Conservator Tank: A small reservoir mounted above the main tank. It holds a reserve of oil. As the main oil volume expands and contracts with temperature changes, the conservator accommodates this change, preventing direct contact between the main tank oil and the atmosphere.

Breather: An attachment on the conservator tank. It contains silica gel, a moisture-absorbing desiccant. As air enters and leaves the tank due to oil volume changes, the silica gel removes moisture, preventing water vapor from contaminating the insulating oil.

Bushings: Large, insulated structures (usually ceramic or porcelain) that allow high-voltage conductors to pass through the grounded tank cover safely, providing a critical level of insulation and physical separation.

Buchholz Relay: A critical gas-sensing protective device installed in the pipe connecting the main tank and the conservator tank. It detects slow-developing faults by collecting small amounts of gas generated by the oil breakdown. It can trip an alarm or shut down the transformer in case of rapid gas accumulation.

Tap Changer: Used to adjust the turns ratio, allowing the utility to regulate the output voltage within a narrow band. This can be done off-load or via an On-Load Tap Changer (OLTC), which adjusts the voltage while the transformer is running.

Real-World Applications and Critical Role

Power transformers are the enabling technology for the scale and efficiency of the modern power grid.

Ultra-High Voltage Transmission

Integration of Remote Power Generation Case Study. In large nations, nuclear, coal, and hydroelectric power plants are frequently situated far from the centers of population. Power from a hydroelectric dam could be generated at 22 kV. GSU transformers reduce current by more than 20 times by instantly stepping this up to 400 kV or 500 kV. Because of the consequent decrease in power loss (I²R), long-distance transmission is now financially viable. Step-down transformers at the receiving end incorporate the power into local systems.

Heavy Industrial Loads

Case Study: Steel and Arc Furnace Operations. Industrial complexes using arc furnaces require massive, stable currents at low voltages. A dedicated substation receives the utility's transmission voltage. Large industrial transformers then step the voltage down (e.g., from 13.8 kV to hundreds of volts) while providing continuous high-current output to support furnace demands.

Grid Interconnection and Stability

Interconnecting transformers enable grid flexibility and stability. They allow power to be diverted between networks during peak demand or outages. This capability is essential to prevent blackouts and to maintain frequency stability, especially as renewable energy sources fluctuate.

Selection Criteria and Technical Specifications

Selecting a power transformer is a complex engineering task guided by international standards such as IEC and ANSI/IEEE.

KVA Rating (Power Capacity)

The KVA or MVA rating defines the maximum apparent power the transformer can deliver continuously without overheating. The rating must exceed the expected load and include a margin for future growth.

Impedance Voltage (%)

The percentage impedance is essential for fault management. Low impedance improves voltage regulation but results in extremely high fault currents. High impedance limits fault current but causes a greater voltage drop under load.

Insulation Class and Temperature Rise

The insulation class (A, B, F, H) defines allowable temperature levels. Transformers are designed for specific temperature rise values (e.g., 55°C rise) to ensure long insulation life, typically 40 years.

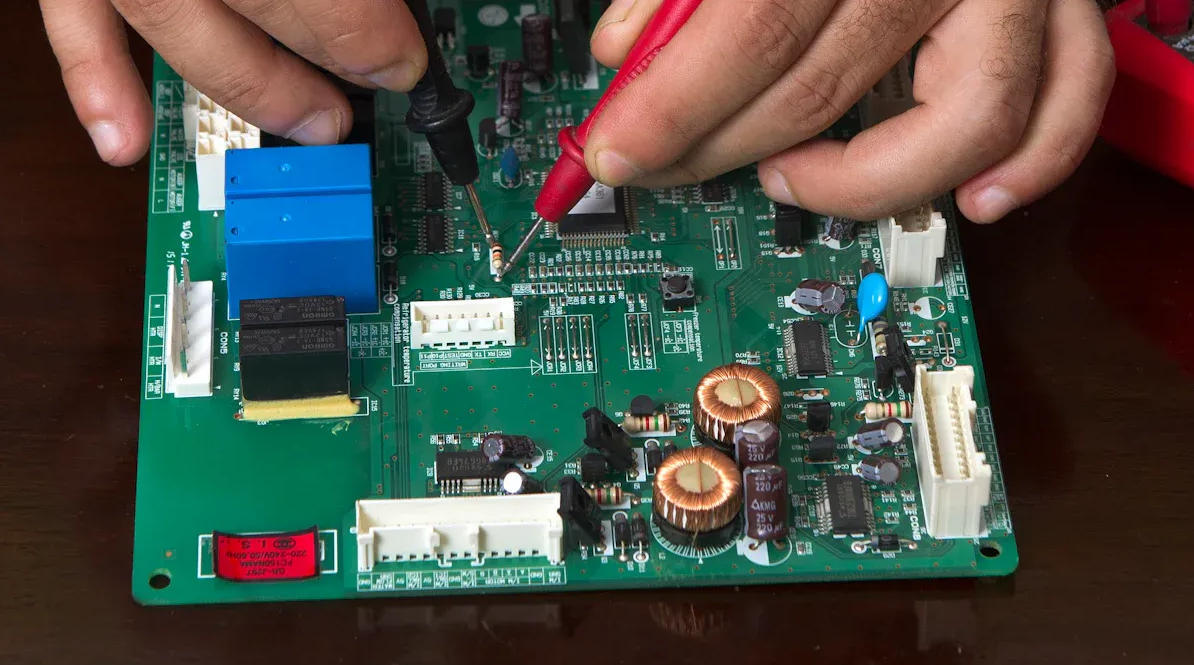

Installation, Electrical Testing, and Maintenance

Proper installation and rigorous maintenance are essential to achieving the expected 40–60 year lifespan of a power transformer.

Essential Installation Protocols

Grounding: A robust grounding system protects personnel and equipment by safely diverting fault currents.

Vibration Control: Isolation pads or specialized mounts reduce the transmission of mechanical hum.

Oil Handling: Oil must be handled under controlled conditions. Moisture entering the oil significantly reduces dielectric strength.

Advanced Maintenance and Oil Analysis

Routine maintenance includes specialized electrical and chemical tests.

The most crucial diagnostic procedure is dissolved gas analysis, or DGA. Predictive maintenance is made possible by gas levels that signal overheating, partial discharge, or arcing.

Oil Dielectric Strength Test: Assesses the oil's ability to insulate. Contamination is indicated by low strength.

Oil Furan Analysis: Quantifies the byproducts of winding insulation paper's breakdown. Advanced insulation aging is indicated by high furan levels.

Electrical Testing

Megger Test for Insulation Resistance: Evaluates the level of insulation between ground and windings.

Winding Resistance Test: Determines the windings' DC resistance in order to identify any damaged conductors or problems with connections.

Verifies the voltage ratio using the Turns Ratio Test (TTR). Deviations indicate problems with the tap changer or windings.

Troubleshooting Common Operational Issues

Common transformer issues and their causes are outlined below.

Low oil level, overload, cooling system failure (fans or pumps), or high ambient temperature are the usual causes of high oil temperature. Reducing load, inspecting cooling equipment, replacing low oil, and using DGA to find internal faults are some solutions.

Loud, Unusual Noise: A transformer typically emits a continuous hum. Unusually loud cracking or humming noises could be a sign of severe internal arcing, loose winding clamps, or loose core laminations. If external structures are loose, tighten them; however, if internal arcing is suspected, shut down right away and run TTR and DGA tests.

Low oil dielectric strength: Suggests contamination or moisture intrusion (such as a failed breather). Oil filtration, degassing, and silica gel replacement in the breather are the solutions.

The Buchholz Relay Alarm Trip signals the buildup of gas due to a small amount of overheating or partial discharge. For DGA to identify the fault, oil samples must be collected right away.

Conclusion

As the silent regulator of the global energy supply, the power transformer is an essential device. It effectively modifies voltage levels by using electromagnetic induction to address the fundamental problem of long-distance transmission.

It is crucial to comprehend all of its vital parts, from the core and windings to the sophisticated cooling and protection mechanisms. Long service life and the dependability of the global power grid are guaranteed by proper maintenance, particularly DGA and electrical testing.