How Magnetic Sensors Actually Work: A Simple Guide for Beginners

Magnetic sensors convert invisible magnetic fields into electrical signals we can measure and use. In fact, these remarkable devices detect the magnitude and variations of magnetic fields with impressive accuracy - the most sensitive type, called SQUID, remains unmatched in its detection capabilities. Whether you realize it or not, we interact with magnetic field sensors daily in our smartphones, cars, and household appliances.

Among the different types of magnetic sensors, Hall Effect sensors are specifically the most widely used for sensing magnetic fields, though there are several other important varieties. Furthermore, magnetic proximity sensors enable contactless detection that powers everything from automotive systems to medical devices. The technology continues to evolve rapidly, with the worldwide magnetic sensor market expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 5.1 percent between 2022 and 2028. In this guide, I'll break down how these fascinating sensors work, the different types available, and their countless real-world applications.

What is a magnetic sensor and why it matters

At their core, magnetic sensors are specialized devices that detect and measure magnetic fields, converting this information into electrical signals that can be processed and analyzed. These remarkable components act as translators between the invisible world of magnetism and the readable realm of electrical data that powers our technology-driven society.

Definition and basic concept

Magnetic sensors are devices that detect the magnitude of magnetism generated by magnets or electric currents. These sensors respond to magnetic fields and their variations, serving as essential tools across numerous engineering applications.

Essentially, these sensors function by detecting changes in magnetic properties and converting them into measurable electrical signals. Unlike many other types of sensors, magnetic detectors don't directly measure physical properties like temperature or pressure. Instead, they identify changes or disturbances in magnetic fields that have been created or modified.

The basic characteristics that make magnetic sensors so valuable include their ability to perform non-contact measurements, high reliability, exceptional durability, and impressive measurement sensitivity. Additionally, magnetic fields can penetrate many non-metallic materials, allowing these sensors to work without direct contact with target objects.

How magnetic sensors convert magnetic fields into signals

The conversion process varies depending on the specific type of sensor technology employed. However, all magnetic sensors share the fundamental purpose of transforming magnetic field data into electrical signals that electronic circuits can process.

Some sensors, like Hall effect sensors, generate voltage in response to magnetic fields. When electrons move through a conductor in the presence of a magnetic field, they experience the Lorentz force, which creates a voltage perpendicular to both the current direction and magnetic field. This voltage is directly proportional to the strength of the magnetic field.

In contrast, magnetoresistive sensors operate on a different principle. Rather than generating voltage, these sensors exhibit changes in electrical resistance when exposed to magnetic fields. This property allows them to detect even subtle variations in magnetic field strength.

Other technologies, such as coil-based sensors, detect variations in magnetic flux density. When a magnet approaches a coil, it increases the magnetic flux density, generating induced electromotive force and current. Once movement stops, these induced forces cease, allowing the sensor to detect the ratio and direction of change in magnetic flux density.

Common uses in everyday devices

The versatility of magnetic sensors has led to their widespread adoption across multiple industries and applications:

Automotive applications: These sensors detect position in brake systems, steering mechanisms, and gear systems while providing crucial inputs to vehicle electronic control units. They're also vital for wheel speed detection in anti-lock braking systems.

Consumer electronics: Smartphones and tablets incorporate magnetic sensors for compass functionality and navigation features. These miniaturized sensors help determine orientation relative to Earth's magnetic field.

Industrial automation: Position sensing of machinery parts, valves, doors, fluid levels, and tools makes these sensors indispensable in manufacturing processes. They enable precise control in robotic systems by detecting joint positions.

Security systems: Magnetic sensors detect when doors or windows are opened, playing a crucial role in home security.

Medical applications: From sophisticated MRI machines to implantable sensors, magnetic sensing technology has become integral to modern healthcare.

The non-contact nature of magnetic sensing offers significant advantages over mechanical alternatives, making these devices ideal for harsh environments where physical switches would quickly degrade. Moreover, their ability to operate reliably across various conditions has cemented their position as cornerstone components in today's information society.

Types of magnetic sensors and how they work

Magnetic field detection comes in various forms, with each sensor type offering unique advantages for specific applications. From simple coil-based designs to quantum-level detection systems, the evolution of magnetic sensors demonstrates remarkable technological advancement.

Coil-based sensors

As the most basic magnetic sensor technology, coil-based sensors detect changes in magnetic flux density through a simple yet effective mechanism. When a magnet approaches a coil, the magnetic flux density increases, generating an induced electromotive force and current in the coil. Once the magnet stops moving, no induced force occurs since there's no change in flux density. This straightforward design makes these sensors particularly durable and suited for detecting moving ferromagnetic objects like gear teeth, sprockets, or rotating machine parts. The output voltage directly corresponds to the target's movement speed, making them valuable in velocity sensing applications.

Reed switches

Reed switches operate through an elegantly simple contact-based design—two ferromagnetic blades hermetically sealed within a glass tube containing inert gas. This sealed environment prevents corrosion and allows operation in nearly any setting. When exposed to a magnetic field, these blades become magnetized and attract each other, creating physical and electrical contact. Upon removing the magnetic field, they separate and break the circuit.

These switches consume no power when in the open state and can perform reliably for billions of operations. They come in three main configurations:

Form A: Normally Open (NO), closes when magnetic field is present

Form B: Normally Closed (NC), opens when magnetic field is present

Form C: Combines both functions, redirecting current between contacts

Reed switches excel in security systems, transportation, consumer electronics, and medical equipment due to their reliability, zero standby power consumption, and ability to function in harsh environments.

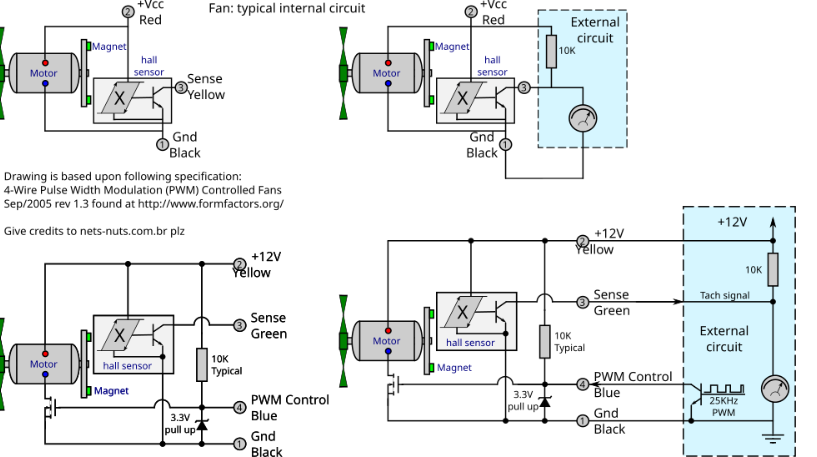

Hall effect magnetic sensors

Unlike induction-based sensors, Hall effect sensors can detect static magnetic fields without requiring movement. These sensors function based on a principle discovered by Edwin Hall in 1879. When a magnetic field is applied perpendicular to a current-carrying semiconductor, the Lorentz force deflects moving electrons, creating a voltage (Hall voltage) proportional to the field's strength.

Most modern Hall sensors include built-in amplification circuits, logic switching, and voltage regulators to enhance sensitivity and improve performance across various power supply conditions. These versatile devices find applications in automotive systems for position sensing, current measurement without requiring large transformers, and even detecting ferromagnetic materials when paired with a biasing magnet.

Magnetoresistive sensors (AMR, GMR, TMR)

Magnetoresistive technology detects magnetic fields through resistance changes in specialized materials. Three primary variants exist, each offering progressively higher sensitivity:

Anisotropic Magnetoresistive (AMR) sensors use single-layer ferromagnetic materials with an MR ratio of approximately 3%. Giant Magnetoresistive (GMR) sensors incorporate alternating ferromagnetic and non-magnetic conductive layers, achieving an MR ratio around 12%. Tunnel Magnetoresistive (TMR) sensors represent the most advanced technology, utilizing quantum tunneling through an insulating layer between two ferromagnetic layers to achieve remarkable MR ratios up to 100%.

Consequently, TMR sensors generate output signals approximately 20 times stronger than AMR sensors and 6 times stronger than GMR sensors. This extraordinary sensitivity, combined with extremely low power consumption (as low as 0.001-0.01 mA) and excellent temperature performance (up to 200°C), makes TMR technology ideal for high-precision applications.

SQUID sensors for ultra-sensitive detection

Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices (SQUIDs) represent the pinnacle of magnetic sensing technology. These quantum sensors offer unmatched sensitivity, capable of measuring magnetic flux lower than 1 µΦ₀ or magnetic fields as weak as 1-3 fT per band unit. For perspective, PTB's wideband magnetometer achieves noise levels down to 150 attotesla.

SQUIDs function as a closed superconducting loop containing Josephson junctions that respond to changes in external magnetic fields by producing measurable voltage variations. Their extraordinary sensitivity makes them invaluable for applications requiring detection of extremely weak magnetic fields, including biomagnetism research, quantum computing, geophysics, and magnetic microscopy.

Nevertheless, practical implementation presents challenges—SQUIDs typically require cooling with liquid helium to maintain their superconducting state, making systems bulky and costly. Despite these limitations, SQUIDs remain the reference standard for ultra-low magnetic field detection, with no other sensor technology approaching their sensitivity level.

Understanding the working principle of magnetic field sensors

The fundamental physics behind magnetic sensors reveal fascinating principles that enable their remarkable detection capabilities. Understanding these core mechanisms helps explain how these devices transform invisible magnetic phenomena into measurable electrical signals.

Magnetic flux and how it's measured

Magnetic flux density serves as the fundamental quantity that magnetic field sensors detect. This property measures the amount of magnetic field passing through a given area. As magnetic field sensors operate, they detect changes in this flux, which indicates the presence of magnetic materials or variations in electromagnetic environments. Through carefully designed magnetic circuits, engineers can convert displacement measurements into direct magnetic flux readings. The magnetic flux density varies inversely with the displacement, creating a predictable relationship that sensors can interpret.

Lorentz force and Hall voltage

The Hall effect remains one of the most important principles in magnetic sensing technology. When electrons move through a conductor exposed to a magnetic field, they experience the Lorentz force, which pushes them perpendicular to both the current direction and the magnetic field. This force creates a voltage differential across the conductor known as the Hall voltage. This voltage can be expressed mathematically as:

VH = (B × I) / (n × q)

Where VH is the Hall voltage, B represents magnetic flux density, I is current flow, n refers to charge carrier density, and q is the charge of carriers. This relationship allows Hall effect sensors to determine both the strength and polarity of magnetic fields with remarkable precision.

Magnetoresistance and electron spin

Magnetoresistive sensors function primarily through resistance changes when exposed to magnetic fields. The resistance change (ΔR) relates to the magnetic field (B) through a sensitivity coefficient: ΔR = S × B. Different types of magnetoresistive sensors utilize various physical phenomena. Anisotropic magnetoresistive (AMR) sensors exhibit small resistance changes, whereas giant magnetoresistive (GMR) sensors demonstrate substantially larger changes, offering greater sensitivity for precise measurements.

Tunneling effect in TMR sensors

Tunnel magnetoresistance represents a purely quantum mechanical phenomenon occurring in magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs). These structures consist of two ferromagnetic layers separated by a thin insulating barrier only a few nanometers thick. According to quantum mechanics, electrons can "tunnel" through this barrier, with the tunneling probability depending on the relative magnetization directions of the ferromagnetic layers. When the magnetizations align in parallel, electron tunneling occurs more readily than in the antiparallel state, creating distinctly different resistance states. TMR sensors can achieve remarkable magnetoresistance ratios of up to 200% at room temperature, making them extraordinarily sensitive to magnetic field changes.

Advantages and limitations of magnet sensors

Beyond their impressive detection capabilities, magnetic sensors offer numerous practical advantages that make them ideal for challenging environments. Let's examine their strengths and limitations to better understand their real-world applications.

Strengths: durability, cost, non-contact sensing

Magnetic field sensors excel through their non-contact measurement capability, allowing them to detect positions without physical contact or wear. This feature makes them exceptionally durable with very long service times. Besides detecting through non-magnetic walls (including stainless steel, aluminum, plastic, or wood), these sensors remain tamper-proof and highly resistant to interference.

The durability advantage extends to harsh environments—magnetic proximity sensors withstand shock, vibration, dirt, and moisture conditions that would quickly disable alternatives like optical encoders. Notably, they maintain reliable performance even in high-dynamic processes with switching frequencies reaching up to 5 kHz.

Cost-effectiveness represents another significant benefit, primarily due to their simple construction and long operational life. The variable operating distance achieved by selecting appropriate magnets provides flexibility in installation and application.

Limitations: interference, range, temperature sensitivity

Despite their advantages, magnetic field sensors face several challenges. Magnetic interference remains their primary limitation—nearby electronic devices, motor shafts, and brakes producing fields of 500-2000 gauss can cause partial or complete malfunction. External magnetic fields from sources like elevators or inductive heating systems may compromise measurement accuracy.

Generally, magnetic sensors show notable temperature dependence, which affects their accuracy during temperature fluctuations. This sensitivity requires compensation mechanisms for applications with significant temperature variations.

Operating range presents another constraint, as these sensors can only detect magnetic fields within certain distances based on field strength and sensor sensitivity. Furthermore, components to be detected must be equipped with at least one magnet, and the sensing range depends on the mounting direction of the magnet.

Applications of magnetic proximity sensors in real life

From vehicles to smartphones, magnetic proximity sensors are indispensable in today's technology landscape. These versatile components drive innovation across multiple sectors through their reliable detection capabilities.

Automotive: speed and position detection

Magnetic field sensors excel in automotive applications, detecting everything from crankshaft position to wheel speed. They enable critical functions in anti-lock braking systems, electronic steering controls, and transmission operations. In fact, these sensors have become vital for electric vehicles, monitoring batteries and motors while optimizing energy efficiency.

Consumer electronics: smartphones and appliances

Magnetic sensors serve as the backbone for compass functionality in smartphones and tablets. First appearing in the iPhone 3GS (2009) and HTC Dream (2008), these sensors primarily enable navigation applications. Currently, they're essential for optical image stabilization in smartphone cameras, with this market alone projected to reach $176 million.

Medical and industrial uses

In medical equipment, magnetic sensors enable precise control in ventilators, infusion pumps, and kidney dialysis machines. For industrial applications, they power uninterruptible supplies for computer servers, welding systems, and large variable frequency motors.

Robotics and automation

Magnetic sensors provide contactless proprioceptive feedback in robotic systems, offering high-precision measurements of angular position and rotational speed. Their compact size, immunity to contaminants, and reliability make them ideal for motion control across factory automation and material handling systems.

Conclusion

Magnetic sensors have certainly proven themselves as remarkable devices that bridge the invisible world of magnetism with our technology-driven society. Throughout this guide, we've seen how these sensors transform magnetic fields into electrical signals through various mechanisms like the Hall effect, magnetoresistance, and quantum tunneling. Undoubtedly, each type offers unique advantages for specific applications, from simple reed switches to ultra-sensitive SQUID sensors.

The non-contact nature of magnetic sensing stands out as a significant advantage, making these sensors ideal candidates for harsh environments where physical switches would quickly deteriorate. Additionally, their durability, cost-effectiveness, and ability to detect through non-magnetic materials give them an edge over alternative sensing technologies. Still, we must acknowledge their limitations regarding magnetic interference, temperature sensitivity, and operating range.

These sensors now surround us in ways we rarely notice. Your smartphone compass, car's anti-lock brakes, home security system, and even medical devices rely on magnetic sensing technology. The market continues to grow rapidly as engineers find new applications across industries.

Looking ahead, magnetic sensor technology shows no signs of slowing down. Advancements in materials science and quantum physics will likely yield even more sensitive and efficient sensors. Whether detecting minute changes in Earth's magnetic field or monitoring critical systems in electric vehicles, these devices will remain essential components of our technological future. The next time you use your smartphone compass or your car's electronic systems, remember the fascinating magnetic sensors working silently behind the scenes.

Joydo is a leading global distributor and wholesaler of electronic components with over 18 years of industry experience.

Get your first sensor now: https://www.joydo-ele.com/inquiry.html

Founded in 2006, Joydo Electronics Co., Limited specializes in integrated circuits, resistors, capacitors, transistors, connectors, relays, modules, semiconductors, memory and advanced chips (automotive, medical, AI, drone, and new energy). We operate a global B2B cross-border platform featuring top brands: TI, NXP, ST, ON, ADI, Intel, Microchip, AMD, JST, Molex, HRS, ERNI, FCI, Samtec, and more.

FAQs

How do magnetic sensors function?

Magnetic sensors detect and measure magnetic fields, converting them into electrical signals. They work through various mechanisms such as the Hall effect, magnetoresistance, or quantum tunneling, depending on the type of sensor. These devices can detect both static and changing magnetic fields, making them versatile for numerous applications.

What are the main advantages of using magnetic sensors?

Magnetic sensors offer several benefits, including non-contact measurement capability, high durability, and cost-effectiveness. They can detect through non-magnetic materials, withstand harsh environments, and provide long service life. These sensors are also resistant to interference from dirt, moisture, and vibrations, making them ideal for challenging industrial applications.

Are there any limitations to magnetic sensor technology?

While magnetic sensors are highly versatile, they do have some limitations. They can be affected by magnetic interference from nearby electronic devices or strong magnetic fields. Temperature sensitivity can impact their accuracy in fluctuating conditions. Additionally, their operating range is limited by the strength of the magnetic field and the sensor's sensitivity.

In what everyday devices can we find magnetic sensors?

Magnetic sensors are ubiquitous in modern technology. They're found in smartphones for compass functionality, in cars for speed and position detection in various systems, in home security devices, and in many household appliances. They're also crucial in industrial automation, robotics, and medical equipment like MRI machines and implantable sensors.

How accurate are magnetic sensors compared to other sensing technologies?

The accuracy of magnetic sensors can vary depending on the specific type and application. Generally, magnetoresistive sensors offer higher sensitivity and accuracy compared to induction-based sensors, as they can measure static magnetic fields directly and produce less noise. Advanced technologies like TMR (Tunnel Magnetoresistive) sensors can achieve remarkably high precision, making magnetic sensors highly competitive in many applications requiring accurate measurements.