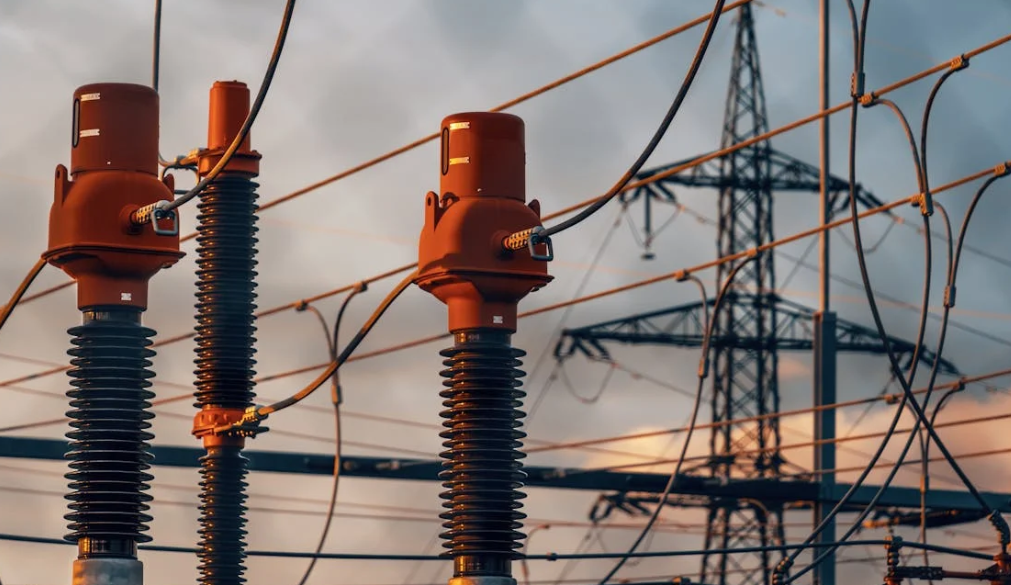

Current Transformer Accuracy Classes: Metering vs. Protection Explained

In the world of high-voltage power systems, direct measurement of electrical current is often impossible. The currents flowing through transmission lines and industrial busbars can range from hundreds to thousands of amperes. Connecting a standard measuring instrument directly to these high currents would destroy the instrument and present a lethal hazard to personnel. This is where the Current Transformer (CT) becomes essential.

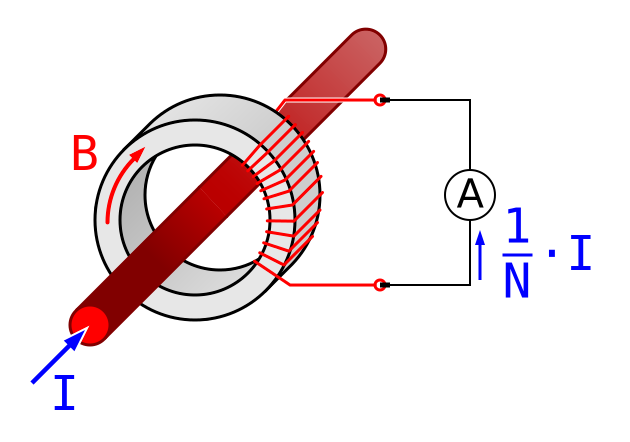

A Current Transformer is a specialized type of instrument transformer. Its primary purpose is to produce a reduced current in its secondary winding that is strictly proportional to the high current flowing in its primary winding. By stepping down the current to a standard, safe value—typically 1 Ampere or 5 Amperes—the CT allows standard meters and protective relays to monitor and protect massive power systems safely.

Beyond just measurement, the CT provides a critical safety function: Galvanic Isolation. It physically separates the high-voltage primary circuit (which might be at 138,000 volts) from the low-voltage secondary circuit (connected to the control room panels). This isolation protects human operators and sensitive electronic equipment from high-voltage transients and faults.

Working Principles and Fundamental Theory

The operation of a current transformer relies on the same laws of electromagnetic induction as a standard power transformer, but its application is different.

The Series Connection

Unlike a voltage transformer, which is connected in parallel across the lines, the primary winding of a current transformer is connected in series with the load. This means that the full line current flows through the CT's primary side. The impedance of the CT primary is designed to be virtually zero so that it does not restrict or change the current flowing to the load.

Current Transformation Ratio

The core principle is defined by the turns ratio. However, in a CT, the current ratio is the inverse of the voltage ratio. If we want to step down the current, we must step up the voltage (conceptually), which means the secondary winding has more turns than the primary.

For example, consider a 1000:5 CT. This ratio means that when 1000 Amperes flow through the single turn of the primary conductor, 5 Amperes will flow through the secondary winding. If the primary has 1 turn (the busbar itself), the secondary will have 200 turns to achieve this ratio. The relationship is strictly linear within the CT's rated range: if primary current drops to 500 Amps, secondary current drops to 2.5 Amps.

The Concept of Burden

In CT terminology, the load connected to the secondary winding is not called "load" but is referred to as Burden. The burden is the total impedance (resistance plus inductance) of the secondary circuit. This includes the resistance of the connecting wires, the resistance of the meter or relay coils, and the internal resistance of the CT secondary winding itself.

Burden is critical because a CT has a limited capacity to push current through this resistance. If the burden is too high (e.g., wires are too long or too thin), the CT voltage will rise to try and push the current, leading to saturation and measurement errors. Burden is usually expressed in Volt-Amperes (VA) or Ohms at a specific power factor.

Critical Safety Warning: The Danger of Open Circuits

This is the single most important safety rule when working with current transformers. A Current Transformer secondary circuit must never be left open while the primary is energized.

In a normal power transformer, leaving the secondary open is safe; it just means no load is drawn. But in a CT, the primary current is forced through the primary winding regardless of what happens on the secondary side. This primary current creates a strong magnetic flux in the core.

When the secondary is closed (connected to a meter), the secondary current creates an opposing magnetic flux that cancels out most of the primary flux. This keeps the core voltage low and safe.

However, if the secondary circuit is opened (broken wire or disconnected meter), this opposing flux disappears. The full primary current now acts as a magnetizing current. The magnetic flux in the core shoots up to extremely high levels, causing the core to saturate instantly. This rapid change in flux induces a massive voltage spike across the open secondary terminals. This voltage can reach thousands of volts.

The consequences are severe:

Lethal Electric Shock: The high voltage can arc across the open terminals or through the insulation to a technician, causing death.

Insulation Failure: The voltage spike can burn out the CT's internal insulation, destroying the unit.

Fire: The core will overheat rapidly due to excessive iron losses, potentially causing a fire or explosion.

Safety Protocol: Before removing any meter or relay from a live CT circuit, a technician must always apply a shorting link or shorting block across the secondary terminals. This maintains the closed loop and keeps the voltage safe.

Construction Types and Classifications

Current transformers come in various shapes and sizes, optimized for different installation environments and accuracy requirements.

Window (Toroidal) Transformers

The window or toroidal CT is the most common type. It consists of a ring-shaped core with the secondary winding wrapped around it. It has no primary winding built-in. Instead, the primary conductor (a cable or busbar) is passed through the center "window" of the ring. This passing conductor acts as a one-turn primary. These are robust, inexpensive, and widely used in switchgear cabinets.

Bar-Type Transformers

In a bar-type CT, the primary conductor is an integral part of the assembly. It consists of a solid copper or aluminum bar that is permanently surrounded by the core and secondary winding. The ends of the bar have terminals for bolting directly into the high-current power path. These are used where the mechanical stresses of short-circuit currents are very high, as the integrated bar structure is very strong.

Wound Primary Transformers

Used for lower current ratios (e.g., 5:5 or 10:5), the wound primary CT has a primary winding with multiple turns wrapped around the core, just like the secondary. This multiple-turn primary is needed to generate enough magnetic flux to drive the secondary accurately when the line current is very low.

Split-Core Transformers (Retrofit Friendly)

The split-core CT is designed for existing installations where you cannot turn off the power to disconnect cables. The core is cut into two distinct halves. It can be opened, placed around a conductor, and then clamped shut. This feature makes it incredibly popular for energy audits, building management systems, and temporary power monitoring. While convenient, split-core CTs are generally slightly less accurate than solid-core types due to the tiny air gaps where the core halves meet.

Accuracy Classes: Metering vs. Protection

Not all CTs are built the same. They are engineered for two distinct purposes: Metering (Measurement) and Protection (Relaying). The requirements for these two jobs are opposites.

Metering Class CTs

Metering CTs are designed for high accuracy during normal operation. They are used for billing (revenue metering) where every kilowatt-hour counts.

The Saturation Factor: A unique feature of metering CTs is that they are designed to saturate (stop working linearly) if the current gets too high. This is a safety feature for the connected meter. If a short circuit occurs and current jumps to 20 times normal, the CT core saturates and limits the secondary current. This prevents the sensitive meter mechanism from being destroyed by the surge.

Accuracy Designations:

Class 0.1 and 0.2: These are high-precision grades. Class 0.1 means the error is no more than 0.1%. These are used for critical revenue metering at power plants and inter-tie points.

Class 0.5: This is the standard for industrial revenue metering.

Class 1.0 and 3.0: These are used for general indication, such as simple panel ammeters where a 1% or 3% error is acceptable.

Protection Class CTs

Protection CTs drive the relays that trip circuit breakers during a fault. During a short circuit, the current might be 20 or 50 times the normal rating. The protection CT must not saturate during this event. It must faithfully reproduce this huge current so the relay can measure it correctly and decide to trip.

Accuracy Designations (ANSI/IEEE):In North America, protection class is often designated by a code like C100 or C400. The "C" stands for Calculated (meaning the leakage flux is negligible). The number (100, 200, 400, 800) represents the maximum secondary voltage the CT can deliver to the burden without exceeding a 10% error margin at 20 times the rated current. A C800 CT is much larger and stronger than a C100 CT.

Accuracy Designations (IEC):In Europe and Asia, the designation might look like 5P20. The "5" stands for 5% composite error. The "P" stands for Protection. The "20" is the Accuracy Limit Factor, meaning the CT will remain accurate up to 20 times the rated primary current.

Installation Best Practices

Proper installation ensures measurement accuracy and personnel safety.

Polarity and Direction

Polarity is critical for power calculation and directional protection. If a CT is installed backward, the meter will see power flowing in the reverse direction.

Terminals are marked to indicate direction. In the IEEE standard, the primary terminals are marked H1 and H2. The secondary terminals are marked X1 and X2. The rule is simple: Current flowing into H1 (Primary) will produce a current flowing out of X1 (Secondary).

In the IEC standard, the markings are P1 and P2 for primary, and S1 and S2 for secondary. Current entering P1 results in current leaving S1. Technicians must verify the direction of power flow and match the CT orientation accordingly.

Single-Point Grounding

The secondary circuit of a CT must be grounded, but it must be grounded at only one point. This is usually done at the first terminal block in the control cabinet or at the CT itself.

Why Ground? Grounding prevents the secondary circuit from floating to a high potential due to capacitive coupling with the high-voltage primary. It is a vital safety measure.Why Only One Point? If you ground the circuit at two different locations (e.g., at the CT and at the Relay), ground currents can flow through the CT secondary wiring. These stray ground currents will add to or subtract from the measurement signal, causing errors and potentially causing relays to trip incorrectly (nuisance tripping).

Wiring and Burden Check

The wire connecting the CT to the meter must be sized correctly. Thin wire has high resistance. If the wire run is long (e.g., from the switchyard to the control room), the resistance of the wire might exceed the CT's rated burden capacity.

Technicians perform a Burden Calculation before installation. They add up the resistance of the wire (loop resistance) and the resistance of the relay coils. This total must be less than the CT's nameplate burden rating. If the burden is too high, the solution is to use thicker wire (e.g., upgrade from #12 AWG to #10 AWG) or use a CT with a higher burden rating.

Testing and Commissioning Procedures

Before a CT is put into service, it undergoes specific tests to verify its condition.

Ratio and Polarity Test

This test confirms the CT is actually transforming current at the stated ratio (e.g., 1000:5) and that the polarity markings are correct. A voltage is applied to the secondary winding, and the induced voltage on the primary is measured (Voltage Method), or a heavy current is injected into the primary and the secondary is measured (Current Method).

Excitation (Saturation) Test

This test plots the saturation curve of the CT. Voltage is applied to the secondary winding and increased in steps. The exciting current drawn by the CT is measured at each step.

This creates a curve showing the "Knee Point." The Knee Point is the voltage at which the CT begins to saturate. This test is vital for protection CTs to prove they can handle high fault voltages without failing. It also confirms that the correct class of CT (Metering vs. Protection) is installed. A metering CT will have a low knee point; a protection CT will have a high knee point.

Insulation Resistance Test

Just like power transformers, the insulation between the windings and the ground must be checked using a Megger. This ensures that the winding insulation has not been damaged during transport or installation.

Loop Resistance Test

Once the entire circuit is wired, a loop resistance test injects current through the loop to verify that all connections are tight and that the total burden is within limits.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problems with CTs can manifest as incorrect meter readings or protective relay malfunctions.

Issue: Zero Reading on AmmeterLikely Cause: The secondary circuit is shorted out somewhere before the meter. Or, the shorting block used during maintenance was left in the "shorted" position.Action: Check the shorting blocks. Check for wiring shorts. Do not disconnect wires until you are sure the primary is de-energized or the circuit is safely shorted elsewhere.

Issue: Low Reading on AmmeterLikely Cause: High resistance connection or a partial short circuit in the secondary wiring. Alternatively, the CT ratio might be selected incorrectly (e.g., a 2000:5 CT used on a 1000A line).Action: Perform a burden test. Check all terminal screws for tightness. Verify nameplate ratio.

Issue: Incorrect Power Factor or Reverse PowerLikely Cause: Polarity error. The CT is installed backward on the conductor, or the S1/S2 wires are swapped at the meter terminals.Action: Verify physical orientation of H1/P1. Verify wiring traces. Swap polarity at the terminal block if confirmed wrong.

Issue: Nuisance Tripping of Ground Fault RelaysLikely Cause: CT saturation during motor starting. Or, multiple ground points on the CT secondary neutral wire.Action: Check for single-point grounding. Verify CT saturation class is adequate for the inrush current.

Conclusion

The Current Transformer is a device of precision and protection. It bridges the gap between the lethal power of the high-voltage grid and the delicate control systems that manage it. From the robust Bar-type CTs in generating stations to the versatile Split-Core units in building retrofits, they enable us to see and control the flow of energy.

Understanding the distinction between Metering and Protection classes, strictly adhering to polarity rules, and observing the cardinal safety rule—never open-circuit the secondary—ensures that these devices function accurately and safely. Whether for billing revenue or protecting a substation from catastrophic faults, the humble CT is an indispensable component of the modern electrical infrastructure.